How Thriving Arctic Shipping Threatens the Food and Future of Inuit Communities along the Northwest Passage

By Ayuka Kawakami

November 9, 2025

In the Canadian Arctic, the frozen world that sustains the Inuit is melting away. For generations, the frozen sea has been their culture, their highway, and their refrigerator, connecting them to essential food sources like seals, whales, muskoxen, and even polar bears. When the ice solidifies in the fall, it signals the start of the hunting season for skilled dog mushers and hunters like Devon Manik in Resolute Bay. But this year, the signal was delayed by more than a month. While the Canadian Arctic is warming at a rate three to four times faster than the rest of the planet, the sea ice has refused to freeze reliably, turning a seasonal route into a deadly trap.

“We travel on sea ice from 10km to 200km, depending on what we are hunting. The sea freezes by the end of September. Now, it’s already November, and the last day of the sun. It should be minus 30 °C, and we should be hunting out on the sea ice. But the sea ice is still too thin for us to travel on it safely. We have been waiting too long.”

Devon Manik – Inuit hunter in Resolute Bay

The very crisis threatening the Inuit’s food security is ushering in an era of shipping expansion. Bryan Comer, the director of the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) marine program, observes that thinning ice is an invitation for the shipping industry: “The Arctic is becoming even more accessible as we have less sea ice each year, and there’s a lot of commercial pressure. There are natural resources like oil and gas. There’s a ton of fishing activity. There are mining operations, and then there are cruise operations.” This commercial surge, heavily reliant on a dirty heavy fuel oil (HFO), creates a devastating feedback loop: The HFO contributes to the accelerating ice melt and threatens the very wildlife the Inuit depend on, as burning HFO releases significantly more climate-warming black carbon (BC), and its viscous nature makes spills nearly impossible to contain and risks ecological catastrophes.

Heavy Fuel Oil: The Dirty Secret of Arctic Shipping

Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO), a thick, poor-quality, bottom-of-the-barrel byproduct of the oil refining process, is largely unusable across most transportation sectors. Even with its low quality and high viscosity, HFO remains the fuel of choice for much of the global shipping industry, primarily because it is cheaper than cleaner alternatives such as distillate fuel.

This reliance on cheap HFO comes at a high environmental cost, particularly from the emission of black carbon (BC). BC is tiny, dark soot particles in the engine exhaust with an extremely strong climate-warming effect. Dr. Maria Sand and her team at the University of Oslo found that BC not only directly warms the atmosphere, but also, through its deposition on the Arctic’s pristine snow and ice, dramatically accelerates melting, creating a dangerous feedback loop. “Maritime traffic is, in fact, the sole source of black carbon emissions in the pristine but vulnerable Arctic waters,” Commer says.

Dr. Maria Sand and her team also found that BC released in the Arctic tends to stay in the lower atmosphere, settling onto the surface. The team’s analysis further suggests that absorption of heat by BC deposited on snow, and the associated impacts on sea ice, snow cover, and clouds, are responsible for two-thirds of the Arctic’s surface temperature increase. Critically, the warming impact per unit of BC emitted in the Arctic is almost five times greater than an equivalent emission at midlatitudes, meaning even a small increase in shipping traffic in the region could have devastating climate consequences.

The regional impacts are already being felt, the Inuit hunter Devon Manik noted, describing the changing conditions and their immediate consequence: “We see fewer seals for sure. We had huge storms all summer and fall; it gusted to 120km/h all fall and killed a whole bunch of seals. 14 dead seals were found in the bay here alone.”

This cheap, thick fuel poses an incredible danger in the delicate polar region. According to ICCT, an HFO spill presents a much greater challenge in remote Arctic regions, where response personnel and equipment are far away, and cleanup efforts would also have to contend with Arctic weather and seasonal darkness. The grim reality is that a single HFO spill could have devastating and lasting effects on fragile Arctic marine and coastal environments.

Operating ships in the Arctic comes with great risks, especially navigating the ice-filled Northwest Passage, which can be challenging. And the risks of an accident and an HFO spill only increase as shipping traffic increases in that area, especially when ships are coming through that area for the first time. “Each year, we see more and more ships doing it for the very first time. Who’s going to be the ones that are going to be the first responders? It’s the communities that live there who are putting themselves at risk and exposing themselves to toxic fuels,” Comer warns.

“I think it’s important to think about who really is being exposed to the risk and what they have in that matter in the first place,”

Bryan Comer – ICCT Director of Marine Program

The stakes could not be higher for the Indigenous communities who call this area home. The choice to use the world’s dirtiest fuel in the world’s most vulnerable environment is not just an economic calculation, but a profound transfer of catastrophic risk onto the Indigenous people and the health of the entire Arctic ecosystem.

“Everybody in the Inuit communities knows that they depend on a clean ocean environment for harvesting and for exercising their harvesting rights. And so if there is a spill, it will severely disrupt culture, being, community cohesion, environmental ecosystems, and the ability for Inuit to harvest.”

Andres Dumbrille – Former sustainable shipping specialist at WWF-Canada

Dumbrille explained a major fuel spill as an “absolutely catastrophic” immediate event for Arctic communities, while deeming black carbon emissions a “slow-moving catastrophe.”

The melting ice has opened a door, but for whom, and at what cost to those who have always called this home?

For the Inuit communities scattered across this vast, remote territory, shipping is not a luxury, but a critical infrastructure, akin to roads and the electricity grid; communities simply “can’t do without it,” Dumbrille says. The supply ships are the literal lifeline, bringing in everything from food to building materials.

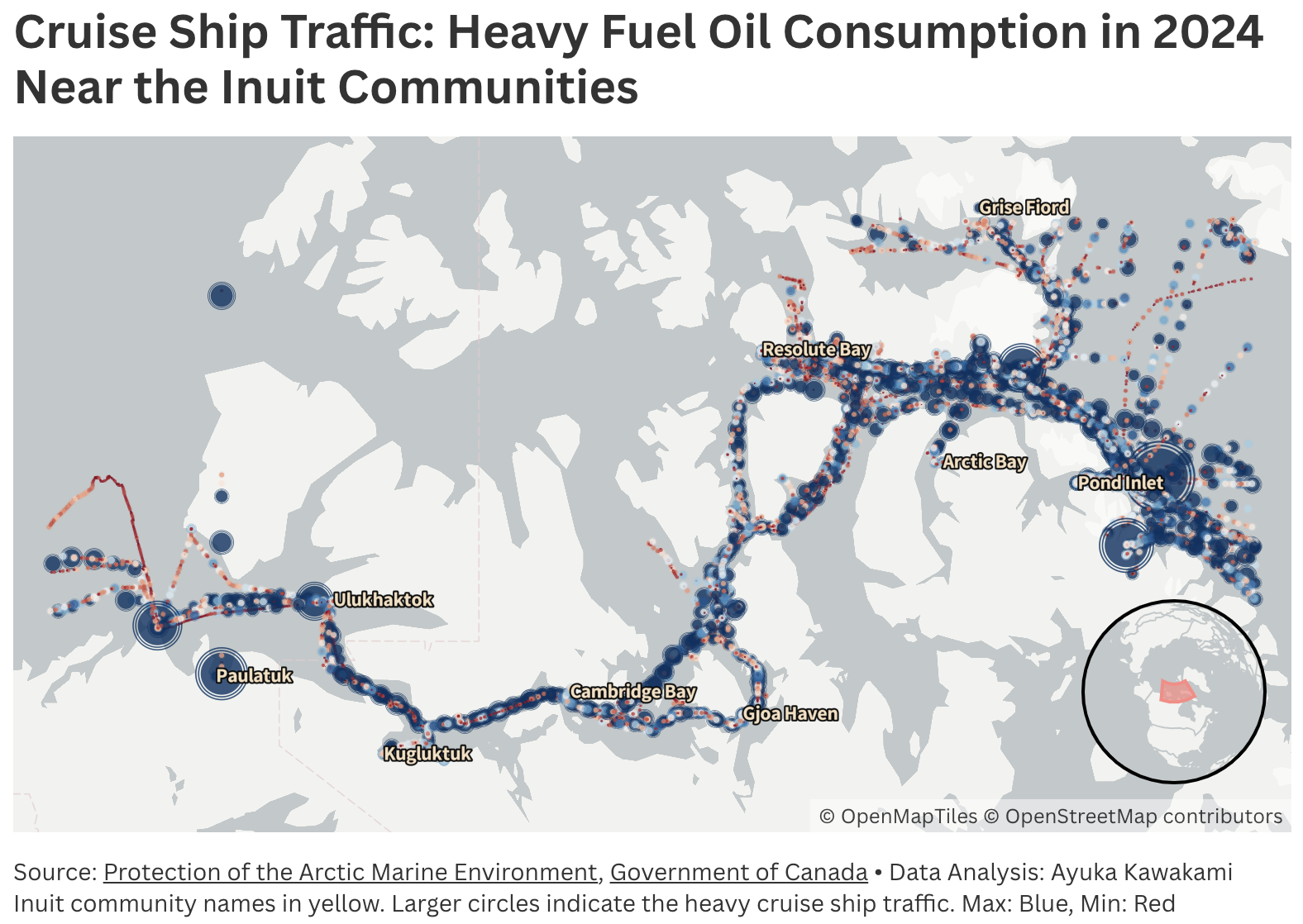

Yet, this vital waterway is also becoming a traffic lane for different kinds of vessels. There is a lot of commercial pressure to operate in the Canadian Arctic, driven by economic and resource extraction interests, as well as tourism. This includes cargo ships seeking a shortcut through the Northwest Passage, connecting continents in a newly accessible route, and increasingly, cruise ships that are “now able to operate in areas that previously would have been way too dangerous or not even accessible,” according to Comer.

This influx of tourism raises critical questions about equity and impact. As Dumbrille points out, cruise ships are a “nice to have, not a must to have.” The dramatic increase in cruise ship operations is a direct consequence of receding sea ice, essentially turning an ecological crisis into an economic opportunity for outsiders, Comer explains. The challenge now is to manage this growing, non-essential marine traffic with its attendant risks of pollution, noise, and cultural disruption while protecting the essential shipping routes that are the very foundation of Inuit life.

Polar tourism has boomed due to a surge in visitors, particularly to Antarctica and the Arctic, driven by increased accessibility and greater interest in the “last-chance-tourism” to see the disappearing world. Cruise ship passengers are often environmentally conscious, and many ships offer lectures on topics such as climate change, wildlife, and glaciology.

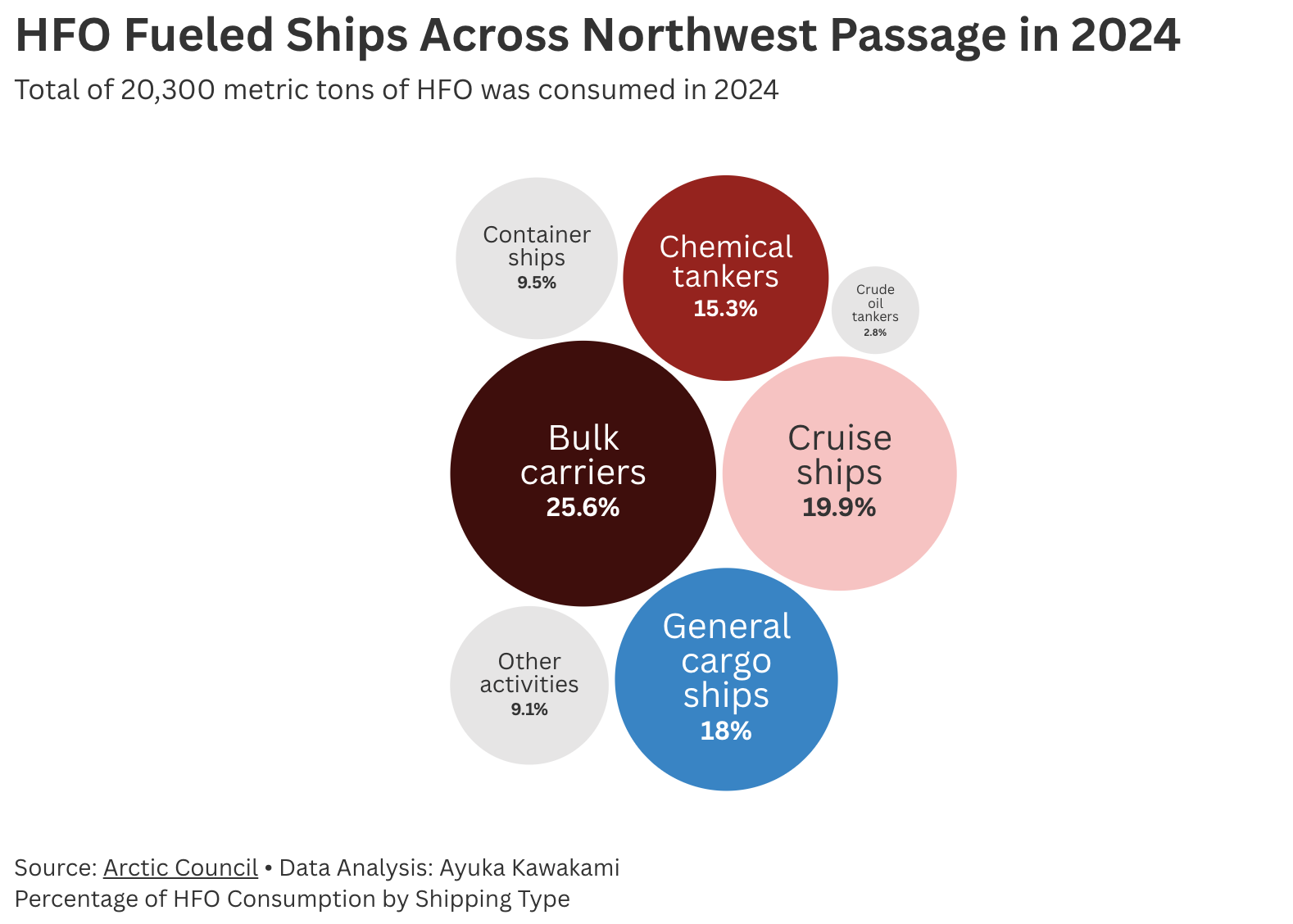

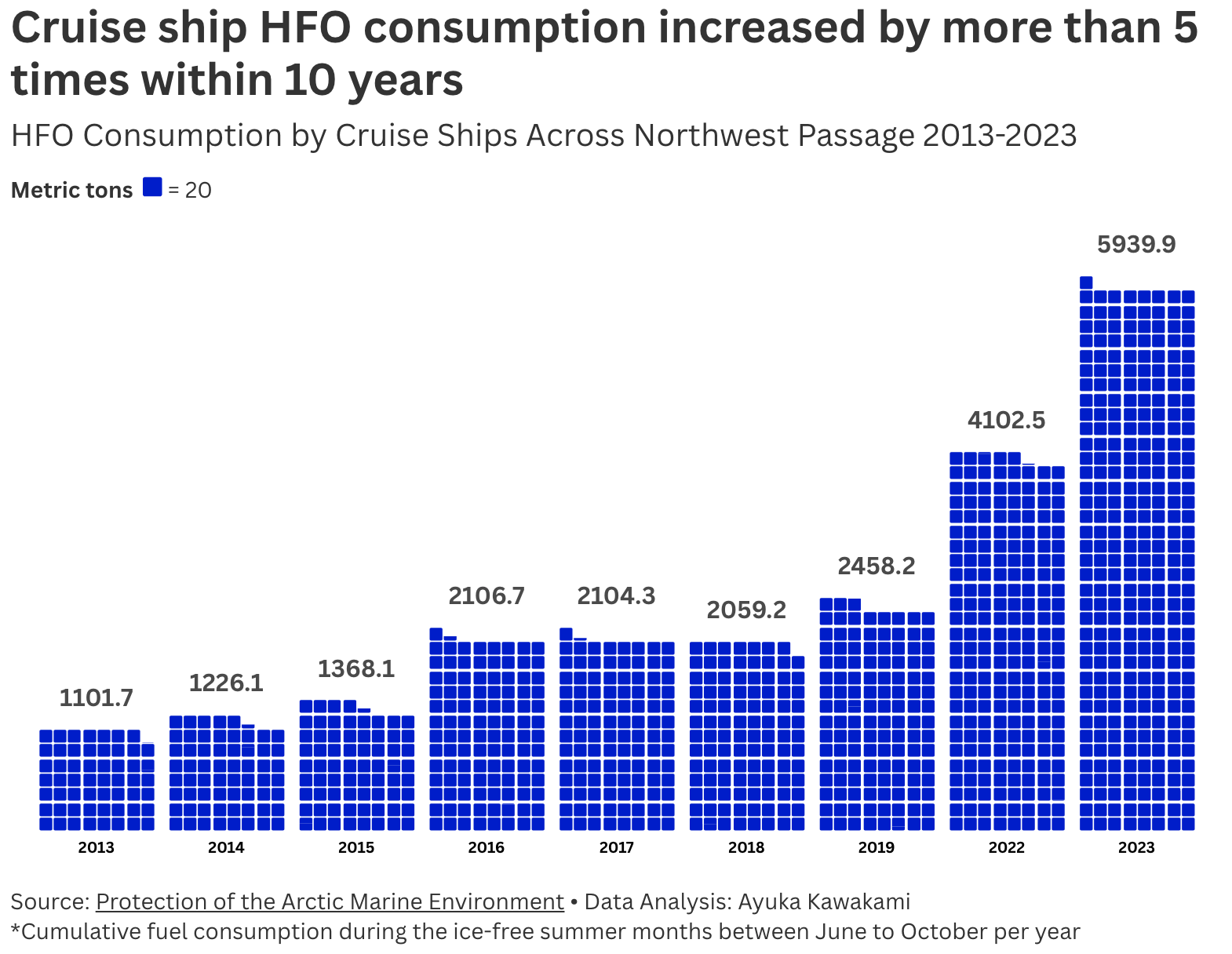

However, ironically, cruise ships are responsible for a significant portion of the increase in HFO over the past decade. HFO is universally recognized as highly harmful to polar environments. Since 2011, HFO has been banned in the Antarctic Ocean, where there is less commercial pressure, with no exemptions or waivers for the shipping industry. While a ban in the Arctic Ocean officially took effect in July 2024, it was implemented with extensive exemptions and waivers, and the environmental gains from the ban are minimal. In fact, HFO use has increased and continues to rise across the Northwest Passage since the ban took effect.

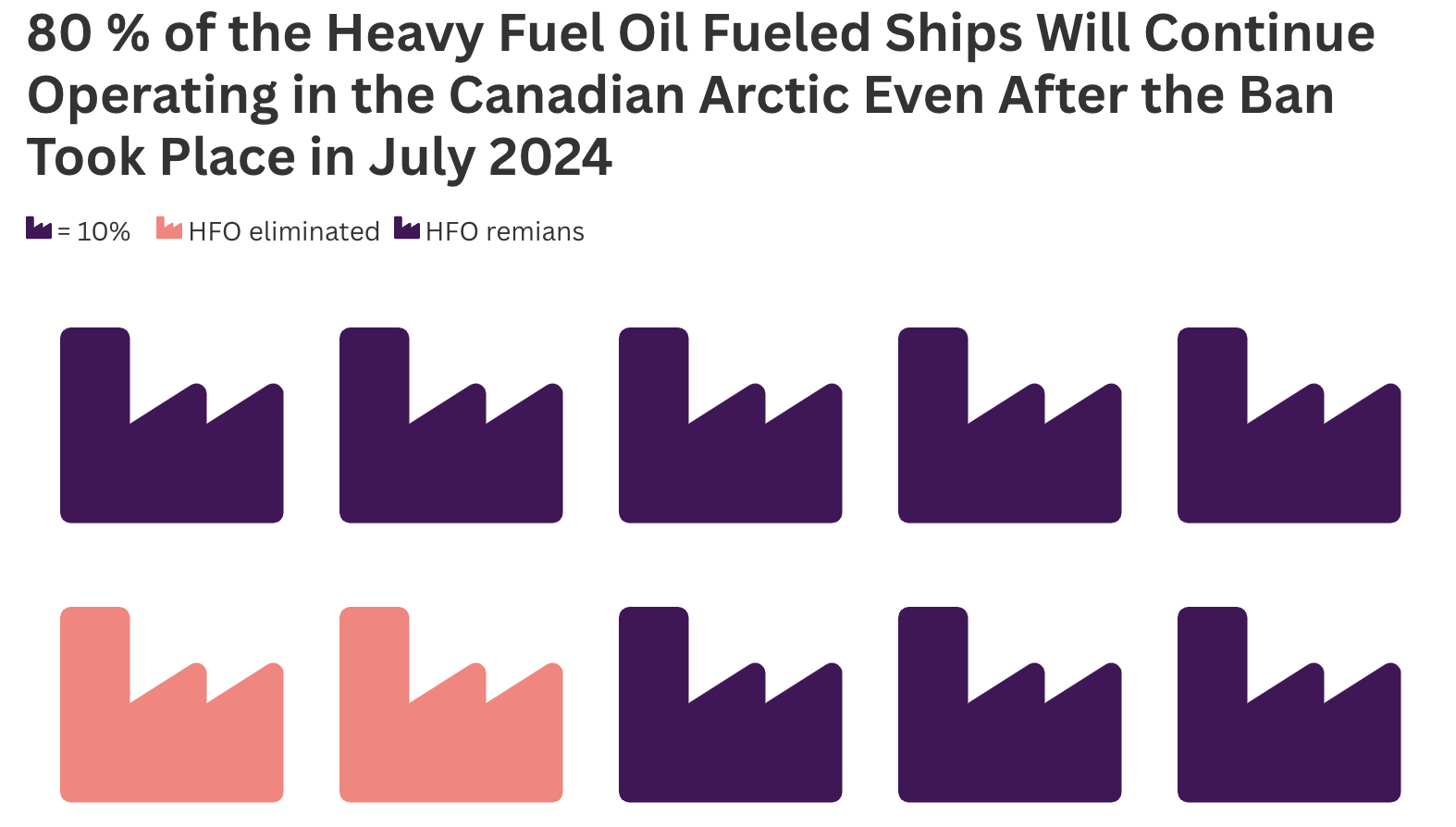

According to an ICCT analysis, the current policy bans only an estimated 16% of HFO use in the Arctic, reducing black carbon by only 5%. Consequently, approximately 74% of HFO-fueled ships can continue sailing across the Arctic Ocean until 2029. The reality is even more concerning in the Canadian Arctic. Dumbrille notes that in the Canadian Arctic, a ban meant to eliminate all HFO is, in practice, allowing approximately 80% of HFO-fueled ships to continue sailing due to these loopholes with waivers and exemptions.

Cruise ships may be unavoidable, and they can benefit local communities, such as through cultural exchange and the sale of local arts and crafts. However, the benefits of cruise traffic have to be clearly articulated, and they have to be quite strong in order to outweigh some of those known consequences. Ultimately, profit for cruise companies and enjoyment of their guests must not come at the expense of the local environment, culture, and safety. The burden of proof is on the luxury sector to demonstrate that its presence does not irrevocably damage the very region it seeks to sell. Dumbrille says the determination of whether cruise traffic “is worth it” must rest solely with the Indigenous residents. “Communities have to weigh these risks and benefits, and only communities can do that,” alongside regional governments and organizations.

In fact, the largest portion of continued HFO use is through the system of exemptions, which primarily applies to newer ships built after 2011. Comer explains that these vessels likely have protected fuel tanks, meaning there is a small gap between the outer hull and the fuel tank so that if they hit something, it “might not” pierce their fuel tank. These exemptions are automatic and “don’t have to be approved,” unlike waivers, which require a formal application to the flag state.

While Canada is taking a firmer stance by generally not issuing waivers in Canadian waters, except for ships engaged in community resupply, the structural exemptions remain a massive loophole. The problem with exemptions is set to get worse: as the Arctic fleet modernizes, even more ships will automatically qualify for these exemptions, Comer warns. This effectively means that the policy, intended to protect the Arctic, may inadvertently incentivize the use of HFO by newer, higher-capacity resource extraction vessels and luxury cruise ships. Because luxury cruise vessels are often newer-built, they qualify for structural exemptions from the ban and will continue cruising until 2029 and even longer.

Drumbrille explains that the Canadian government issued waivers for vessels involved in community resupply as a cost-mitigation measure. This was done to ensure that any increased costs associated with using cleaner fuels weren’t put on communities, whose already high cost of living is heavily reliant on goods brought in by ships. Fuel is a significant portion of a voyage’s price tag—estimated at 20% to 30% of the cost—and switching from HFO to more expensive distillate fuel would have a substantial “knock-on effect on the price of your delivery,” as Dumbrille said. Vessels bringing goods, food, construction materials, and other necessities of life have been given a pass, and they don’t have to switch to cleaner-burning fuels. The consequence, however, is that ships going close to remote indigenous communities are still carrying and using heavy fuel oil, creating a severe spill risk for the communities that rely on these waters. While the Canadian government’s approach to the HFO ban attempts to shield Indigenous communities from price hikes, the resulting waivers have inadvertently concentrated the very environmental risks the ban was meant to eliminate.

Ultimately, the traffic deemed essential resupply carries risks due to waivers, and the traffic deemed non-essential, such as luxury cruises, carries risks due to design exemptions, maintaining the Arctic environmental exposure.

There are solutions

The most effective way to reduce the Arctic’s primary climate pollutant is a simple fuel swap. To reduce black carbon, vessels must switch to cleaner-burning or zero-emission fuels. Dumbrille explains that these options are, in fact, readily available today, known in the marine world as distillate fuels.

The impact of this switch is dramatic: moving from heavy or residual fuels to lighter distillate fuels results in a significant reduction in black carbon, ranging from 50% to 80%. Interestingly, the shipping industry is already equipped for this change. “Shipping is a global business, and the same ships working in the Arctic must operate in Emission Control Areas worldwide. Therefore, they are designed to switch on demand from heavy fuel oil to cleaner fuels all the time. Logistically, it’s simple to run on cleaner fuels, so the entire debate comes down to cost, since distillates are more expensive,” Dumbrille explains.

While a switch to cleaner fuels is critical, the full protection of the Arctic environment and its Indigenous inhabitants demands a broader set of mandatory measures that tackle both physical and auditory pollution. Dumbrille outlines two non-negotiable mandates for the shipping industry. Ships “have to not travel in Inuit harvest areas at all” to prevent disrupting crucial subsistence activities. These areas are essential for the food security and cultural continuity of the communities.

Furthermore, greater attention must be paid to the effects of underwater noise and the growing body of knowledge on how it impacts marine mammals. Noise pollution from vessels can interfere with the communication, navigation, and feeding of species vital to the Arctic ecosystem. “The ships really scare the whales as they don’t like loud sounds. Ships scare off both the Beluga and the narwhal. We’ve seen more ships, so the whales stay away longer,” Manik said.

This forced retreat disrupts the marine mammals’ feeding, migration, and breeding patterns, adding a critical layer of ecological stress to a region already struggling with the rapid pace of climate change. The silence of the whales in their traditional waters is a deafening alarm about the cost of human access.

Shipping operators need to be proactive and engage directly with local communities and land claim organizations in the areas where Inuit communities are located. “This communication should not be merely a formality; they would need to obtain permission to transit through Inuit waters wherever they are. Vessels should place observers on board to guide them through sensitive areas and must actively seek advice from Inuit hunting and trapping organizations on the time of year and where to travel,” Dumbrille explains.

In the increasingly vulnerable Arctic, respect for Indigenous autonomy and deep local knowledge is the only path forward for responsible navigation.

OUR POLAR WORLD IN DATA

© OUR POLAR WORLD IN DATA 2025